needhelp!

02-05 02:36 PM

Hello All,

As per the latest regulations, the employer has to pay for all the labor application cost. My employer has agreed to do my green card, but are little hesitant to pay the cost (due to budget constraint). What legal options/adjustments can I make with my employer so that the cost process is not delayed? Can they deduct part of my salary to bear the cost etc...?

Thanks in advance.

Regards.

Thats illegal. You don't want to get into trouble in future so please do not do that.

As per the latest regulations, the employer has to pay for all the labor application cost. My employer has agreed to do my green card, but are little hesitant to pay the cost (due to budget constraint). What legal options/adjustments can I make with my employer so that the cost process is not delayed? Can they deduct part of my salary to bear the cost etc...?

Thanks in advance.

Regards.

Thats illegal. You don't want to get into trouble in future so please do not do that.

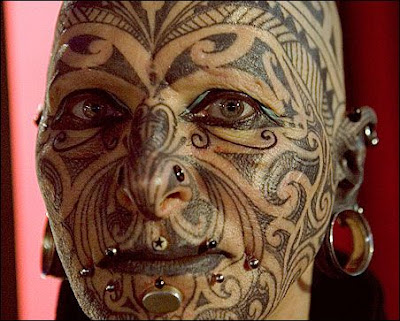

wallpaper tribal/heart-flash-tribal-

abdev

07-21 01:02 PM

PERM (labor certification) process is a requirement from the DOL and has to be fulfilled by the employer. The employer will have to bear the costs of this first step in GC which includes (filing fees, recruitment process, lawyer fees etc). It is illegal for an employer to seek this compensation from the employee. Expenses incurred in I-140 and I-485 need not be compensated by the employer.

In your case, it seems that the employer is ready to help you with all the documentation but is not ready to bear the expenses. You will have to explain to your employer how the GC Process works and the requirements of the PERM process.

In your case, it seems that the employer is ready to help you with all the documentation but is not ready to bear the expenses. You will have to explain to your employer how the GC Process works and the requirements of the PERM process.

mrsr

07-19 10:19 AM

Lets poll and collect the early july filers .. mine was reached at NSc on 2nd July at 9:01. there are way too many threads on it . trying to make a poll to figure out the actual number

2011 Tribal Heart Tattoo 1, flash,

GCisLottery

12-28 09:14 AM

http://www.aclu.org/safefree/general/17444res20040528.html

If government agents question you, it is important to understand your rights. You should be careful in the way you speak when approached by the police, FBI, or INS. If you give answers, they can be used against you in a criminal, immigration, or civil case.

The ACLU's Know Your Rights brochure provides effective and useful guidance in a user-friendly question and answer format. The brochure apprises you of your legal rights, recommends how to preserve those rights, and provides guidance on how to interact with officials.

(Link via AILA)

If government agents question you, it is important to understand your rights. You should be careful in the way you speak when approached by the police, FBI, or INS. If you give answers, they can be used against you in a criminal, immigration, or civil case.

The ACLU's Know Your Rights brochure provides effective and useful guidance in a user-friendly question and answer format. The brochure apprises you of your legal rights, recommends how to preserve those rights, and provides guidance on how to interact with officials.

(Link via AILA)

more...

bodhi_tree

07-06 01:21 PM

My priority date is Jan 04 which was current in June this year. My stupid lawyer sent the whole package of I485 and I765 for me and wife to Chicago address (for family based cases) instead of the Nebraska address where employment based cases are supposed to be sent. The package was mailed around 15th June. I started getting worried since my checks haven't been cashed today so I called the National customer center where they told me about this goof up and said they mailed the package back to the lawyer, last Tuesday.

I don't know if there is anything that can be done at this point to salvage the situation since, with the July bulletin fiasco everything is unavailable now. Really appreciate if any one knowledgeable can comment...any help really

I don't know if there is anything that can be done at this point to salvage the situation since, with the July bulletin fiasco everything is unavailable now. Really appreciate if any one knowledgeable can comment...any help really

Macaca

04-05 08:23 AM

Some paras from Where There's a Cause, There's a Caucus (http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/04/04/AR2007040402757.html), By Zachary A. Goldfarb, Special to The Washington Post, Thursday, April 5, 2007

Every morning in Washington, Rep. Earl Blumenauer (D-Ore.) rides his rusty red-orange Trek bicycle to work on Capitol Hill, a reminder of one of the first things he did when he came to Congress in 1996: create a bike caucus.

With 165 members, the bipartisan Congressional Bike Caucus promotes the use of bicycles as a substitute for cars -- a way to exercise, reduce fossil fuel emissions and improve travel patterns. The caucus shepherded $4 billion for trails, bike paths and pedestrian facilities in a big transportation spending bill in the last Congress.

The bike caucus is just one of the zany-sounding groups that lawmakers have created on Capitol Hill to advance niche interests in Congress. There's no trick to creating a caucus -- or "congressional member organization" -- in the House, where it takes just a letter to the Administration Committee. Nearly 300 have registered. The Senate has far fewer groups, and they don't register at all.

But some caucuses have come to play prominent roles on the front lines of Capitol Hill. The Republican Study Committee has worked to amplify the views of the more conservative wing of the GOP. Since Democrats took control of Congress in January, the Congressional Black Caucus has wielded unusual power, with five members serving as chairmen of House committees.

Every morning in Washington, Rep. Earl Blumenauer (D-Ore.) rides his rusty red-orange Trek bicycle to work on Capitol Hill, a reminder of one of the first things he did when he came to Congress in 1996: create a bike caucus.

With 165 members, the bipartisan Congressional Bike Caucus promotes the use of bicycles as a substitute for cars -- a way to exercise, reduce fossil fuel emissions and improve travel patterns. The caucus shepherded $4 billion for trails, bike paths and pedestrian facilities in a big transportation spending bill in the last Congress.

The bike caucus is just one of the zany-sounding groups that lawmakers have created on Capitol Hill to advance niche interests in Congress. There's no trick to creating a caucus -- or "congressional member organization" -- in the House, where it takes just a letter to the Administration Committee. Nearly 300 have registered. The Senate has far fewer groups, and they don't register at all.

But some caucuses have come to play prominent roles on the front lines of Capitol Hill. The Republican Study Committee has worked to amplify the views of the more conservative wing of the GOP. Since Democrats took control of Congress in January, the Congressional Black Caucus has wielded unusual power, with five members serving as chairmen of House committees.

more...

reddymjm

01-22 01:35 PM

It would be nice if we can co-ordinate and do it in all Major cities at the same time.

2010 free heart tattoo flash. hot

indyanguy

09-03 12:07 AM

Theoretically, it's possible. However, if there is a Ability 2 Pay issue during 485 adjudication, would you be able to take care of it?

more...

Iammontoya

06-05 10:04 AM

first person view? third person?

either way it's kinda complicated, although 3rd person would be easier, for the room would not be moving.

either way it's kinda complicated, although 3rd person would be easier, for the room would not be moving.

hair Hearts Tattoo Flash Book

Blog Feeds

04-26 11:30 AM

On March 19, 2010, the USCIS announced revised filing instructions and addresses for applicants filing an I-131, the Application for Travel Document.

Beginning March 19, 2010 applicants will have to file their applications at the USCIS Vermont Service Center or at one of the USCIS Lockbox facilities.

If you file the I-131 at the wrong location, the USCIS Service Centers will forward it to the USCIS Lockbox facilities for 30 days, until Monday, April 19, 2010. After April 19, 2010, incorrectly filed applications will be returned to the applicant, with a note to send the application to the correct location.

Here is a link to the new filing locations. (http://www.uscis.gov/portal/site/uscis/menuitem.5af9bb95919f35e66f614176543f6d1a/?vgnextoid=1d17aca797e63110VgnVCM1000004718190aRCR D&vgnextchannel=fe529c7755cb9010VgnVCM10000045f3d6a1 RCRD)

More... (http://www.philadelphiaimmigrationlawyerblog.com/2010/03/test_1.html)

Beginning March 19, 2010 applicants will have to file their applications at the USCIS Vermont Service Center or at one of the USCIS Lockbox facilities.

If you file the I-131 at the wrong location, the USCIS Service Centers will forward it to the USCIS Lockbox facilities for 30 days, until Monday, April 19, 2010. After April 19, 2010, incorrectly filed applications will be returned to the applicant, with a note to send the application to the correct location.

Here is a link to the new filing locations. (http://www.uscis.gov/portal/site/uscis/menuitem.5af9bb95919f35e66f614176543f6d1a/?vgnextoid=1d17aca797e63110VgnVCM1000004718190aRCR D&vgnextchannel=fe529c7755cb9010VgnVCM10000045f3d6a1 RCRD)

More... (http://www.philadelphiaimmigrationlawyerblog.com/2010/03/test_1.html)

more...

B+ve

08-28 01:40 PM

As we are sure that the August 2009 visa bulletin EB2 India date movement is due to spill over from higher priority categories, is there any way to find exactly how much visa numbers got spilled over to EB2 India and China?

Thanks,

B+ve

Thanks,

B+ve

hot Tattoos Tattoo flash

TexDBoy

09-05 05:12 PM

Where is your I-140 approved from?

more...

house Broken Heart, Midnight Stars

ncmahesh

07-14 12:15 PM

it was actually recjected it was kept under 221 g in uk , he was returing to india. so he asked embassy to retrun all the papers. so they gave back

tattoo hairstyles Heart tattoo flash

axljovi

02-22 10:00 PM

Hi,

My wife came to US on a L2 dependant visa in June 2007. She applied for EAD and got the same in Oct 2007. She was applying for jobs and both of us had to travel to India for couple of weeks in Dec 2007 due to personal reasons. After coming back, she got a job and is working now using the EAD that she got before the travel to India. Is it legal to work with the EAD she got earlier? I have this doubt because the I-94 with which she got her EAD is not the same as what she/I currently hold.

My wife came to US on a L2 dependant visa in June 2007. She applied for EAD and got the same in Oct 2007. She was applying for jobs and both of us had to travel to India for couple of weeks in Dec 2007 due to personal reasons. After coming back, she got a job and is working now using the EAD that she got before the travel to India. Is it legal to work with the EAD she got earlier? I have this doubt because the I-94 with which she got her EAD is not the same as what she/I currently hold.

more...

pictures Flaming black heart tattoo.

chanduv23

03-21 10:10 PM

I would also like someone to volunteer the meeting lawmaker and other efforts, as I will not be able to do that kind of stuff. I will definitely help mobilize more people into the group.

dresses Tattoo Heart Pictures

maverick_joe

01-08 12:58 PM

If the Given name and the surname on the passport are swapped does this need to be notified to USCIS?I am a July 2007 485 filer./\/

more...

makeup cloud tattoo flash heart

reddog

06-21 12:14 AM

Most of the shots given are booster shots. Two MMR shots?

Varicella needs to be taken twice at 1 month intervals, however most doctors sign and seal the package when you take the first varicella shot and then ask you to come back one month later and take the 2nd shot, if not, you can insist the doctor to do so.

Needed shots are MMR, TD and Varicella, all others are Age unappropriate for us(atleast the applicants and spouses).

Varicella needs to be taken twice at 1 month intervals, however most doctors sign and seal the package when you take the first varicella shot and then ask you to come back one month later and take the 2nd shot, if not, you can insist the doctor to do so.

Needed shots are MMR, TD and Varicella, all others are Age unappropriate for us(atleast the applicants and spouses).

girlfriend heart tattoo flash. heart

srisai122

12-30 04:06 AM

Company A filed my I-140 and it got approved, however I have not been provided with copy of the approval notice. I don't have the receipt number either. In this case, is it possible to obtain the copy of I-140 thru FOIA (Freedom of Information Act)?

Thank you for the help.

Thank you for the help.

hairstyles makeup vintage heart tattoo.

Macaca

03-25 07:23 AM

Some paras from An Opening for Democrats (http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/03/23/AR2007032301585.html), By David S. Broder (http://projects.washingtonpost.com/staff/email/david+s.+broder/), Sunday, March 25, 2007

Six years of Republican control in Washington have taken a toll on the country -- and the GOP is paying the price politically. Instead of the Bush administration ushering in a new era of GOP dominance, as Karl Rove hoped, it has set the stage for a Democratic resurgence.

That turnabout was implicit in the results of the 2006 midterm election, when Democrats took back narrow majorities in the House and Senate and captured the majority of governorships. And it is reinforced by a massive poll released last week by Andrew Kohut and the Pew Research Center for the People and the Press.

The survey of 2,007 people, conducted in December and January, depicts a dramatic shift in Americans' attitudes, opinions and values between 1994, when Republicans took control of Congress, and now. Most of the change has occurred since George Bush took office in 2001.

The poll, which can be found at http://www.people-press.org, is a treasure trove of information about Americans' views of the parties, government, the world scene, religion, the economy, business, labor and a dozen other topics.

But a word of caution is in order. There is little here that suggests voters' opinion of Democrats is much higher than it was when they lost Congress in 1994. It seems doubtful that Democrats can help themselves a great deal just by tearing down an already discredited Republican administration with more investigations such as the current attack on the Justice Department and White House over the firings of eight U.S. attorneys.

At some point, Democrats have to give people something to vote for. People already know what they're against -- the Republicans.

Six years of Republican control in Washington have taken a toll on the country -- and the GOP is paying the price politically. Instead of the Bush administration ushering in a new era of GOP dominance, as Karl Rove hoped, it has set the stage for a Democratic resurgence.

That turnabout was implicit in the results of the 2006 midterm election, when Democrats took back narrow majorities in the House and Senate and captured the majority of governorships. And it is reinforced by a massive poll released last week by Andrew Kohut and the Pew Research Center for the People and the Press.

The survey of 2,007 people, conducted in December and January, depicts a dramatic shift in Americans' attitudes, opinions and values between 1994, when Republicans took control of Congress, and now. Most of the change has occurred since George Bush took office in 2001.

The poll, which can be found at http://www.people-press.org, is a treasure trove of information about Americans' views of the parties, government, the world scene, religion, the economy, business, labor and a dozen other topics.

But a word of caution is in order. There is little here that suggests voters' opinion of Democrats is much higher than it was when they lost Congress in 1994. It seems doubtful that Democrats can help themselves a great deal just by tearing down an already discredited Republican administration with more investigations such as the current attack on the Justice Department and White House over the firings of eight U.S. attorneys.

At some point, Democrats have to give people something to vote for. People already know what they're against -- the Republicans.

Dr. Barry Post

03-31 11:02 PM

:alien:

Macaca

11-11 08:15 AM

Extreme Politics (http://www.nytimes.com/2007/11/11/books/review/Brinkley-t.html) By ALAN BRINKLEY | New York Times, November 11, 2007

Alan Brinkley is the Allan Nevins professor of history and the provost at Columbia University.

Few people would dispute that the politics of Washington are as polarized today as they have been in decades. The question Ronald Brownstein poses in this provocative book is whether what he calls “extreme partisanship” is simply a result of the tactics of recent party leaders, or whether it is an enduring product of a systemic change in the structure and behavior of the political world. Brownstein, formerly the chief political correspondent for The Los Angeles Times and now the political director of the Atlantic Media Company, gives considerable credence to both explanations. But the most important part of “The Second Civil War” — and the most debatable — is his claim that the current political climate is the logical, perhaps even inevitable, result of a structural change that stretched over a generation.

A half-century ago, Brownstein says, the two parties looked very different from how they appear today. The Democratic Party was a motley combination of the conservative white South; workers in the industrial North as well as African-Americans and other minorities; and cosmopolitan liberals in the major cities of the East and West Coasts. Republicans dominated the suburbs, the business world, the farm belt and traditional elites. But the constituencies of both parties were sufficiently diverse, both demographically and ideologically, to mute the differences between them. There were enough liberals in the Republican Party, and enough conservatives among the Democrats, to require continual negotiation and compromise and to permit either party to help shape policy and to be competitive in most elections. Brownstein calls this “the Age of Bargaining,” and while he concedes that this era helped prevent bold decisions (like confronting racial discrimination), he clearly prefers it to the fractious world that followed.

The turbulent politics of the 1960s and ’70s introduced newly ideological perspectives to the two major parties and inaugurated what Brownstein calls “the great sorting out” — a movement of politicians and voters into two ideological camps, one dominated by an intensified conservatism and the other by an aggressive liberalism. By the end of the 1970s, he argues, the Republican Party was no longer a broad coalition but a party dominated by its most conservative voices; the Democratic Party had become a more consistently liberal force, and had similarly banished many of its dissenting voices. Some scholars and critics of American politics in the 1950s had called for exactly such a change, insisting that clear ideological differences would give voters a real choice and thus a greater role in the democratic process. But to Brownstein, the “sorting out” was a catastrophe that led directly to the meanspirited, take-no-prisoners partisanship of today.

There is considerable truth in this story. But the transformation of American politics that he describes was the product of more extensive forces than he allows and has been, at least so far, less profound than he claims. Brownstein correctly cites the Democrats’ embrace of the civil rights movement as a catalyst for partisan change — moving the white South solidly into the Republican Party and shifting it farther to the right, while pushing the Democrats farther to the left. But he offers few other explanations for “the great sorting out” beyond the preferences and behavior of party leaders. A more persuasive explanation would have to include other large social changes: the enormous shift of population into the Sun Belt over the last several decades; the new immigration and the dramatic increase it created in ethnic minorities within the electorate; the escalation of economic inequality, beginning in the 1970s, which raised the expectations of the wealthy and the anxiety of lower-middle-class and working-class people (an anxiety conservatives used to gain support for lowering taxes and attacking government); the end of the cold war and the emergence of a much less stable international system; and perhaps most of all, the movement of much of the political center out of the party system altogether and into the largest single category of voters — independents. Voters may not have changed their ideology very much. Most evidence suggests that a majority of Americans remain relatively moderate and pragmatic. But many have lost interest, and confidence, in the political system and the government, leaving the most fervent party loyalists with greatly increased influence on the choice of candidates and policies.

Brownstein skillfully and convincingly recounts the process by which the conservative movement gained control of the Republican Party and its Congressional delegation. He is especially deft at identifying the institutional and procedural tools that the most conservative wing of the party used after 2000 both to vanquish Republican moderates and to limit the ability of the Democratic minority to participate meaningfully in the legislative process. He is less successful (and somewhat halfhearted) in making the case for a comparable ideological homogeneity among the Democrats, as becomes clear in the book’s opening passage. Brownstein appropriately cites the former House Republican leader Tom DeLay’s farewell speech in 2006 as a sign of his party’s recent strategy. DeLay ridiculed those who complained about “bitter, divisive partisan rancor.” Partisanship, he stated, “is not a symptom of democracy’s weakness but of its health and its strength.”

But making the same argument about a similar dogmatism and zealotry among Democrats is a considerable stretch. To make this case, Brownstein cites not an elected official (let alone a Congressional leader), but the readers of the Daily Kos, a popular left-wing/libertarian Web site that promotes what Brownstein calls “a scorched-earth opposition to the G.O.P.” According to him, “DeLay and the Democratic Internet activists ... each sought to reconfigure their political party to the same specifications — as a warrior party that would commit to opposing the other side with every conceivable means at its disposal.” The Kos is a significant force, and some leading Democrats have attended its yearly conventions. But few party leaders share the most extreme views of Kos supporters, and even fewer embrace their “passionate partisanship.” Many Democrats might wish that their party leaders would emulate the aggressively partisan style of the Republican right. But it would be hard to argue that they have come even remotely close to the ideological purity of their conservative counterparts. More often, they have seemed cowed and timorous in the face of Republican discipline, and have over time themselves moved increasingly rightward; their recapture of Congress has so far appeared to have emboldened them only modestly.

There is no definitive answer to the question of whether the current level of polarization is the inevitable result of long-term systemic changes, or whether it is a transitory product of a particular political moment. But much of this so-called age of extreme partisanship has looked very much like Brownstein’s “Age of Bargaining.” Ronald Reagan, the great hero of the right and a much more effective spokesman for its views than President Bush, certainly oversaw a significant shift in the ideology and policy of the Republican Party. But through much of his presidency, both he and the Congressional Republicans displayed considerable pragmatism, engaged in negotiation with their opponents and accepted many compromises. Bill Clinton, bedeviled though he was by partisan fury, was a master of compromise and negotiation — and of co-opting and transforming the views of his adversaries. Only under George W. Bush — through a combination of his control of both houses of Congress, his own inflexibility and the post-9/11 climate — did extreme partisanship manage to dominate the agenda. Given the apparent failure of this project, it seems unlikely that a new president, whether Democrat or Republican, will be able to recreate the dispiriting political world of the last seven years.

Division of the U.S. Didn’t Occur Overnight (http://www.nytimes.com/2007/11/13/books/13kaku.html) By MICHIKO KAKUTANI | New York Times, November 13, 2007

THE SECOND CIVIL WAR How Extreme Partisanship Has Paralyzed Washington and Polarized America By Ronald Brownstein, The Penguin Press. $27.95

Alan Brinkley is the Allan Nevins professor of history and the provost at Columbia University.

Few people would dispute that the politics of Washington are as polarized today as they have been in decades. The question Ronald Brownstein poses in this provocative book is whether what he calls “extreme partisanship” is simply a result of the tactics of recent party leaders, or whether it is an enduring product of a systemic change in the structure and behavior of the political world. Brownstein, formerly the chief political correspondent for The Los Angeles Times and now the political director of the Atlantic Media Company, gives considerable credence to both explanations. But the most important part of “The Second Civil War” — and the most debatable — is his claim that the current political climate is the logical, perhaps even inevitable, result of a structural change that stretched over a generation.

A half-century ago, Brownstein says, the two parties looked very different from how they appear today. The Democratic Party was a motley combination of the conservative white South; workers in the industrial North as well as African-Americans and other minorities; and cosmopolitan liberals in the major cities of the East and West Coasts. Republicans dominated the suburbs, the business world, the farm belt and traditional elites. But the constituencies of both parties were sufficiently diverse, both demographically and ideologically, to mute the differences between them. There were enough liberals in the Republican Party, and enough conservatives among the Democrats, to require continual negotiation and compromise and to permit either party to help shape policy and to be competitive in most elections. Brownstein calls this “the Age of Bargaining,” and while he concedes that this era helped prevent bold decisions (like confronting racial discrimination), he clearly prefers it to the fractious world that followed.

The turbulent politics of the 1960s and ’70s introduced newly ideological perspectives to the two major parties and inaugurated what Brownstein calls “the great sorting out” — a movement of politicians and voters into two ideological camps, one dominated by an intensified conservatism and the other by an aggressive liberalism. By the end of the 1970s, he argues, the Republican Party was no longer a broad coalition but a party dominated by its most conservative voices; the Democratic Party had become a more consistently liberal force, and had similarly banished many of its dissenting voices. Some scholars and critics of American politics in the 1950s had called for exactly such a change, insisting that clear ideological differences would give voters a real choice and thus a greater role in the democratic process. But to Brownstein, the “sorting out” was a catastrophe that led directly to the meanspirited, take-no-prisoners partisanship of today.

There is considerable truth in this story. But the transformation of American politics that he describes was the product of more extensive forces than he allows and has been, at least so far, less profound than he claims. Brownstein correctly cites the Democrats’ embrace of the civil rights movement as a catalyst for partisan change — moving the white South solidly into the Republican Party and shifting it farther to the right, while pushing the Democrats farther to the left. But he offers few other explanations for “the great sorting out” beyond the preferences and behavior of party leaders. A more persuasive explanation would have to include other large social changes: the enormous shift of population into the Sun Belt over the last several decades; the new immigration and the dramatic increase it created in ethnic minorities within the electorate; the escalation of economic inequality, beginning in the 1970s, which raised the expectations of the wealthy and the anxiety of lower-middle-class and working-class people (an anxiety conservatives used to gain support for lowering taxes and attacking government); the end of the cold war and the emergence of a much less stable international system; and perhaps most of all, the movement of much of the political center out of the party system altogether and into the largest single category of voters — independents. Voters may not have changed their ideology very much. Most evidence suggests that a majority of Americans remain relatively moderate and pragmatic. But many have lost interest, and confidence, in the political system and the government, leaving the most fervent party loyalists with greatly increased influence on the choice of candidates and policies.

Brownstein skillfully and convincingly recounts the process by which the conservative movement gained control of the Republican Party and its Congressional delegation. He is especially deft at identifying the institutional and procedural tools that the most conservative wing of the party used after 2000 both to vanquish Republican moderates and to limit the ability of the Democratic minority to participate meaningfully in the legislative process. He is less successful (and somewhat halfhearted) in making the case for a comparable ideological homogeneity among the Democrats, as becomes clear in the book’s opening passage. Brownstein appropriately cites the former House Republican leader Tom DeLay’s farewell speech in 2006 as a sign of his party’s recent strategy. DeLay ridiculed those who complained about “bitter, divisive partisan rancor.” Partisanship, he stated, “is not a symptom of democracy’s weakness but of its health and its strength.”

But making the same argument about a similar dogmatism and zealotry among Democrats is a considerable stretch. To make this case, Brownstein cites not an elected official (let alone a Congressional leader), but the readers of the Daily Kos, a popular left-wing/libertarian Web site that promotes what Brownstein calls “a scorched-earth opposition to the G.O.P.” According to him, “DeLay and the Democratic Internet activists ... each sought to reconfigure their political party to the same specifications — as a warrior party that would commit to opposing the other side with every conceivable means at its disposal.” The Kos is a significant force, and some leading Democrats have attended its yearly conventions. But few party leaders share the most extreme views of Kos supporters, and even fewer embrace their “passionate partisanship.” Many Democrats might wish that their party leaders would emulate the aggressively partisan style of the Republican right. But it would be hard to argue that they have come even remotely close to the ideological purity of their conservative counterparts. More often, they have seemed cowed and timorous in the face of Republican discipline, and have over time themselves moved increasingly rightward; their recapture of Congress has so far appeared to have emboldened them only modestly.

There is no definitive answer to the question of whether the current level of polarization is the inevitable result of long-term systemic changes, or whether it is a transitory product of a particular political moment. But much of this so-called age of extreme partisanship has looked very much like Brownstein’s “Age of Bargaining.” Ronald Reagan, the great hero of the right and a much more effective spokesman for its views than President Bush, certainly oversaw a significant shift in the ideology and policy of the Republican Party. But through much of his presidency, both he and the Congressional Republicans displayed considerable pragmatism, engaged in negotiation with their opponents and accepted many compromises. Bill Clinton, bedeviled though he was by partisan fury, was a master of compromise and negotiation — and of co-opting and transforming the views of his adversaries. Only under George W. Bush — through a combination of his control of both houses of Congress, his own inflexibility and the post-9/11 climate — did extreme partisanship manage to dominate the agenda. Given the apparent failure of this project, it seems unlikely that a new president, whether Democrat or Republican, will be able to recreate the dispiriting political world of the last seven years.

Division of the U.S. Didn’t Occur Overnight (http://www.nytimes.com/2007/11/13/books/13kaku.html) By MICHIKO KAKUTANI | New York Times, November 13, 2007

THE SECOND CIVIL WAR How Extreme Partisanship Has Paralyzed Washington and Polarized America By Ronald Brownstein, The Penguin Press. $27.95

No comments:

Post a Comment